The Friend-Enemy Distinction

A Theological Critique of the Friend-Enemy distinction in Carl Schmitt's Book "the Concept of the Political"

A couple months ago I set out to understand the works of Carl Schmitt more. You will find a book review that I wrote on his Political Theology here. What I write below should be understood in that context. For more context, on my thoughts on some of these matters, that are loosely related, I wrote an article last summer entitled Lies, More Lies, Damned Lies here.

Introduction:

This essay has a lot to do with Carl Schmitt’s book The Concept of the Political. My main avenue of analysis is his use of the friend-enemy distinction, how Christians should use it, and what a Christian critique of Schmitt’s (and possibly others) use of that distinction is.

The friend-enemy distinction as it is used in Carl Schmitt’s thought and in recent history can play into the hands of both the Left and the Right. The question is not so much about whether the friend-enemy distinction is useful or not, but whether or not the way that it is used in the modern day and particularly in Carl Schmitt is right or wrong. The question is also - what are the limitations of law & conscience on how the state might wield this distinction to persecute a certain people group. To be clear. I am less interested in this essay as to how the ancient pagan Greek philosopher Plato used it, but want to understand how a more recent philosopher, Carl Schmitt used it.

What is the Friend-Enemy Distinction in Carl Schmitt?

When speaking of friends and enemies, Carl Schmitt is not speaking of personal or private friends and enemies. It should be clear that he is speaking of public friends and enemies. In this you should see that how he deals with the matter of friends & enemies is directly related to his political theology. I will quote from Carl Schmitt:

“The enemy is not merely any competitor or just any partner of a conflict in general. He is also not the private adversary whom one hates. An enemy exists only when, at least potentially, one fighting collectivity of people confront a similar collectivity. The enemy is solely the public enemy, because everything that has a relationship to such a collectivity of men, particularly to a whole nation, becomes public by virtue of such a relationship. The enemy is hostis, not inimicus in the broader sense; πόλεμος, not εχθρός. As German and other languages do not distinguish between the private and political enemy, many misconceptions and falsifications are possible. The often quoted ‘Love your enemies’ (Matt. 5:44; Luke 6:27) reads “diligite inimicos vestros,” αγαπατε τους εχθρους υμων, and not diligite hostes vestros. No mention is made of a political enemy. Never in the thousand-year struggle between Christians and Moslems did it occur to a Christian to surrender rather than defend Europe out of love toward the Saracens or Turks. The enemy in the political sense need not be hated personally, and in the private sphere only does it make sense to love one’s enemy, ie, one’s adversary. The Bible quotation touches the political antithesis of good and evil or beautiful and ugly. It certainly does not mean that one should love and support the enemies of one’s on people.”

Carl Schmitt, the Concept of the Political (Chicago: the University of Chicago Press, 1996), 28-29.

Marc Jones and Andrew Willard Jones heartily dispose of Carl Schmitt’s aweful exegesis of the text in this essay. There are politicians who know how to exegete a text. Carl Schmitt is most definitely not one of them. For those who don’t follow the link, most importantly, while Jesus does talk about personal enemies, it does not necessarily exclude political or public enemies. We do find εχθρός used for political enemies in the septuagint.

It should also be stated sooner rather than later that I am not an anabaptist or a pacifist. I am a proponent of just war theory and lawful self-defence. Our magistrates should sort out how exactly they want to apply those theories in 2025. You should be aware though that how you shape up your rationale and the limits thereof, will also determine what kind of atrocities you commit or don’t commit. Ideas have legs, as Schmitt himself learned the hard way.

A Brief Intermission on Why I should not be Writing this Essay (according to Schmitt)

In Schmitt’s system of political theology/theory, I am not allowed to criticize this distinction. I am a pastor. He is allowed to do theology or make a very poor attempt at exegesis. I am not allowed to criticize politics. It is my job in my public facing role to support the state when it declares a public enemy. For example, if the Liberal government of Canada decides that Donald Trump and the US is a public enemy, then it is my duty to go along with that or I am a traitor. Privately I can like Donald Trump, but in my public role I must describe him as a Nazi, even if my own government is the one taking their tactics right out of Schmitt’s rulebook (whether knowingly or unknowingly).

Why did pastors get arrested in the Third Reich? Well, because in their public facing role, they were not always unequivocally supportive of Schmitt’s sovereign.

The Epistemological Foundations for the Friend-Enemy Distinction

Schmitt is less concerned with what the Bible has to say as he is with carving out a neutral space for politics to exist.

I don’t mind the attempt to define a political realm in its own right. But I say that with the conviction that realm of politics is not hermetically sealed off from the authority of God over all things, or the prophetic voice of the church in an evil age. There is not one square inch of all creation, including politics, over which Christ does not declare “mine!”

In section 2 of the Concept of the Political, Schmitt separates between various realms, making a distinction between the political, the aesthetic, the moral. He adds economic distinctions and other distinctions in the following argument. To understand Schmitt, one must understand that the political is its own sphere. It’s interesting that he does not address the sphere of true and false, but I digress, even if my digression is quite important. While good and evil mark the sphere of morality, beautiful and ugly mark the sphere of aesthetics, friend and enemy mark the sphere of politics. So when determining the public friend-enemy, questions of morality or aesthetics don’t matter so much. “Thereby the inherently objective nature and autonomy of the political becomes evident by virtue of its being able to treat, distinguish, and comprehend the friend-enemy antithesis independently of other antitheses.” (p. 27) Hatred should not be a question for Schmitt within the friend-enemy distinction “It can exist theoretically and practically, without having simultaneously to draw upon all those moral, aesthetic, economic, or other distinctions” (p. 28)

So if the political is distinguished from spheres of morality or aesthetics, then who says who the friend or enemy is? Does God have a say?

Schmitt answers this question: “To the state as an essentially political entity belongs the jus belli, i.e., the real possiblity of deciding in a concrete situation upon the enemy and the ability to fight him with the power emanating from the entity.” (p. 45). In light of this, it should be remembered from Schmitt’s Political Theology that “The sovereign is he who decides on the exception.” [Carl Schmitt, Political Theology (Chicago: the University of Chicago Press, tr 1985), 5]

I brought up a number of concerns in my review of Schmitt’s book Political Theology, which should be remembered here. In Schmitt’s thought we find statism, authoritarianism, situational ethics - relativism. Some questions arose. What do we do with the voice of the church in the gates of the city? What do we do with individual protest - the conscience issue? Who decides on the exception? Does the church just engage in the ministry of the Word & prayer, in the ministry of the Word & sacrament, outside of the public square, or only in the quiet of the four walls of the towering cathedral? Or must the church also engage in this ministry of the Word & prayer in the public square?

There is a type of collectivism, group-think, when it comes to the friend-enemy distinction, over which the state is the ultimate arbiter in Schmitt’s thought. The state of emergency, the exception, provides the opportunity for the state as the highest authority in any given society, to determine who is the friend and who is the enemy. This determination is made independent of moral considerations. There may be some lip-service paid to moral considerations. But it ends there.

War

This brings us to the question of war. War is one of the expressions of the friend-enemy distinction playing out in real time. Of course, the political does not reside in the battle itself (p. 37), but the political is found in being able to distinguish a friend from an enemy.

“The concept of humanity is an especially useful ideological instrument of imperialist expansion, and in its ethical-humanitarian form it is a specific vehicle of economic imperialism. Here one is reminded of a somewhat modified expression of Proudhon’s: whoever invokes humanity wants to cheat. To confiscate the word humanity, to invoke and monopolize such a term probably has certain incalculable effects, such as denying the enemy the quality of being human and declaring him to be an outlaw of humanity; and a war can thereby be driven to the most extreme inhumanity.”

Schmitt, Carl. The Concept of the Political. Translated by George Schwab, University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Again, Carl Schmitt writes: “The justification for war does not reside in its being fought for ideals or norms of justice, but in its being fought against a real enemy. All confusions of this category of friend and enemy can be explained as results of blendings of some sort of abstractions or norms.” (p. 49) So whether a war is fought, is not grounded in eternal norms for justice that are grounded in natural law and enlightened by the Bible, but in the state’s determination that there is an enemy.

Are there moral limitations to how we treat our enemies? If there is no hate or love in war, a war really can be carried out to the greatest inhumanity. But the question is - is that possible and what horrors are made possible by trying to imagine that possibility? Is the ability of a state to declare friends or enemies, limited by the conscience of the citizen? Does the church have a word to say about this in the gates of the city?

We need to leave room for conscientious objectors, draft dodgers, men of conscience who will not fight for a tyrannical/wicked regime.

Here, we can discard the more secular term ‘humanity’ for the more Biblical term ‘imago Dei’.

We also need men, who even though they fight when they believe that conscience compels them to do so, see that the enemy is made in the image of God. Here, we can discard the more secular term ‘humanity’ for the more Biblical term ‘imago Dei’. The resistance that fought in the Netherlands against the tyranny of Nazi Germany, handed down the stories of ‘humanity’, or better, ‘imago dei’, that they saw in their enemies. For example, on numerous occasions, it was noted that Bibles were found in the pockets of dead German soldiers. When you pick up a gun to shoot a man, even if it is in a war, you are putting the bullet in the head of a man who is a son, probably a husband, maybe a dad, a brother, a friend. A man, even in a war, is not a robot, but is made in the image of God.

Conclusion

I have listened to a variety of podcasts on the friend-enemy distinction and I have seen public thinkers quoting Carl Schmitt openly. I see an effort to employ a form of the friend-enemy distinction in modern day Canada.

I have also seen this distinction play a role in modern literature, and it is likely that people are using it in different ways.

I encourage my reader to take my critique of Carl Schmitt’s use of the friend-enemy seriously and to analyze how the problems in Carl Schmitt may arise in different modern day expressions of authoritarianism. Remember that in the midst of all the variations of authoritarianism and statism that raise their ugly mugs in our dissident, apostate, and wicked culture, God really has called together a people who are free in Christ (I Peter 2:16), free in Christ, free to do what is right and holy and lovely.

We should always test the various views that we run into with the Word of God, which is as we find in 2 Corinthians 10:3–6, directs us in this manner:

“For though we walk in the flesh, we are not waging war according to the flesh. For the weapons of our warfare are not of the flesh but have divine power to destroy strongholds. We destroy arguments and every lofty opinion raised against the knowledge of God, and take every thought captive to obey Christ, being ready to punish every disobedience, when your obedience is complete.”

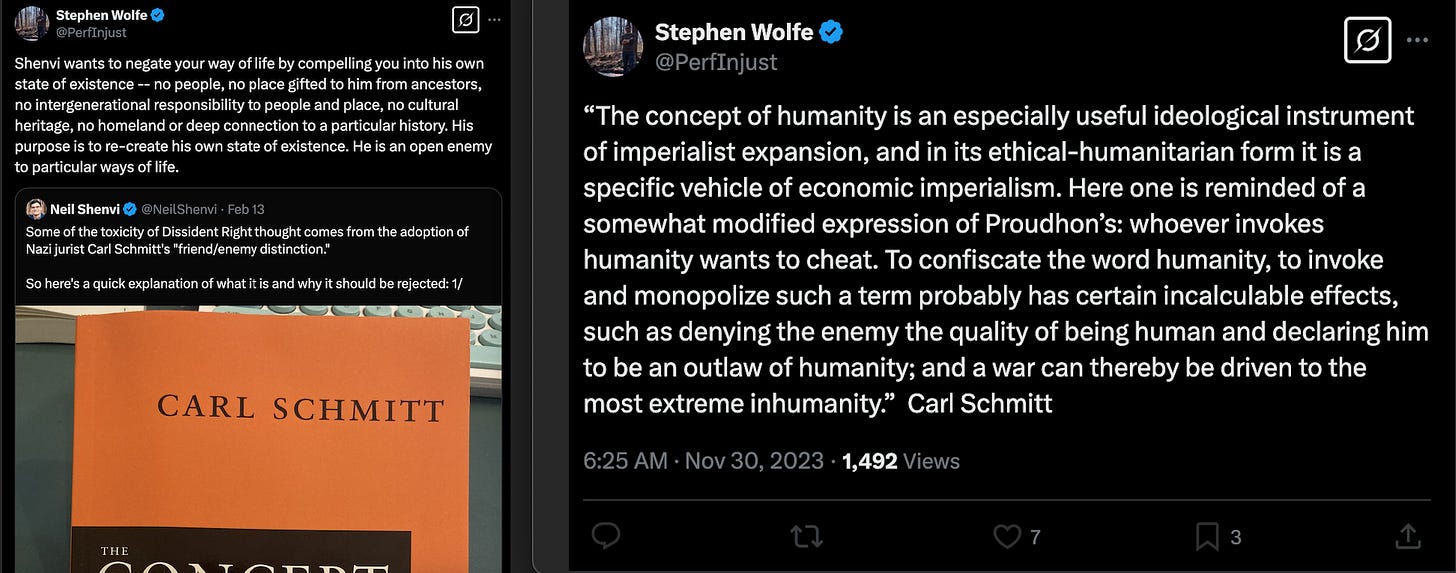

A Brief Addendum on Christian Nationalism

It should be noted that Carl Schmitt is readily used and quoted both on the Left and on the Right. The self-referential movement of Christian Nationalism is a diverse movement, so not all Christian Nationalists are Schmittians. A number of its prominent thinkers openly quote from Carl Schmitt, as I will demonstrate in a list of screenshots below. Take it for what it is and remember that apparently China has learned from Schmitt too. All that said, I think it is fair to cross-examine these guys on why they would use Schmitt and how they would use the friend-enemy distinction.

Photo by Erik Mclean on Unsplash

I'm still digesting this. I'd be interested in you following up with more of your own take on this friend-enemy distinction, how it may have been used, and how it is being used.